Thomas Bo Jensen:

per kirkeby / architecture

Per Kirkeby is best known for his visual art. He did, however, have a life-long passion for architecture that manifested itself in his writing, visual art, and sculptures and culminated in a number of buildings erected in the latter part of his career. The book gives an impression of Per Kirkeby’s overall architecture output and also shows that rather than being an appendix to Per Kirkeby’s visual art, it was a central part of his way of thinking and work as an artist.

The book is the result of several years of research into Per Kirkeby’s comprehensive archives that included numerous conversations between the author and the artist. The many well-preserved drawings from Kirkeby’s childhood and youth have made it possible to document a hitherto unknown context in his artistic universe.

Thomas Bo Jensen is an architect and professor at the Aarhus School of Architecture. He has previously written monographs about the master builder P.V. Jensen-Klint and the architects Inger and Johannes Exner.

Issued: February 2019

Features: 312 pages, full color, hard cover

Format: Large format 30x26 cm

Languages in separate versions:

English version ISBN 978-87-91567-28-9

Danish version ISBN 978-87-91567-30-0

Price: € 60 / DKK 450 Incl. Vat

Excluding forwarding expenses

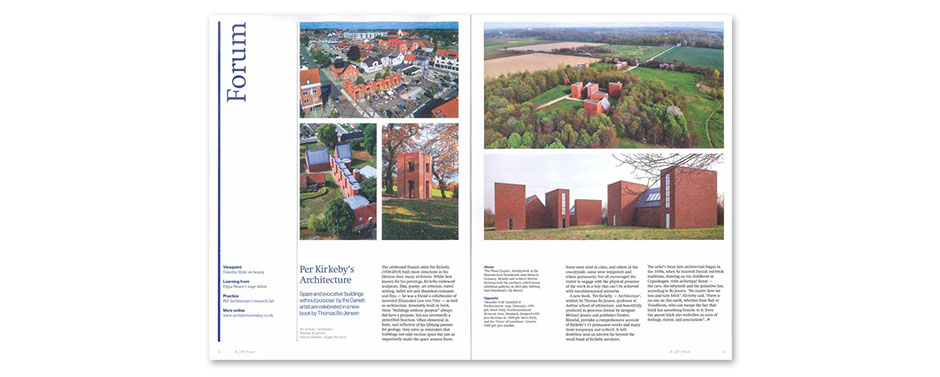

Per Kirkeby Architecture according to Architecture Today, April 2019. Press for large view

Per Kirkeby Architecture according to Arquine, September 2019. Press for large view

Carl Brummer.

Thorvaldsen.

1. The Old Maya, 1971

2. Recollection of a visit at a Lacondon family in the rainforest, 1971

Per had this idea of filming both the Copenhagen Court House and the Carl Brummer houses in the Svanemølle precinct in the evening, when the buildings stood like silhouettes almost like the solidified lava in Myvatn in Iceland, or lit up by both the street lighting and the lights inside the house. At the houses in the Svanemølle precinct, the lights from the windows were an important element. We spent a number of evenings wandering around in the dark. I filmed the garnish mouldings on the Willumsen house in the same way as the ornamentation on the Maya ruins. Per never wrote a script, just a list of what I was to film – and then he left the rest to me.

On his trip to the land of the Mayas, Per had two types of sketchbook with him. His usual sketchbooks of course, but also his 8mm Eumig camera, which he made frequent use of during those years. He not only filmed a lot, he also edited his own films on a small viewer. Per was a member of ABCinema, which a couple of years earlier had occupied the National Film School, where I was a student. So when he wanted to sit and draw, he used to shove the Eumig into my hands and say with a smile: After all, you’ve been to the film school. I would certainly never have been admitted to the film school if I’d shown the film from the land of the Mayas.

Teit Jørgensen

Humlebæk Station (1994)

© Niels Lyksted

Ørestad North

© Niels Lyksted

The Latest Brick Works

(Bielefeld, Kröller-Muller, Bergen) – are for me a step into an area where there is hardly a crush. All of these brick sculptures are transparent, are penetrable thoroughfares that only acquire meaning when one walks through them. They are no longer enclosed, monolithic sculptures, even though photographs may give that impression. A photograph nearly always conveys a shape that is slightly obtuse and dismissive. The experience, on the other hand, will be that precisely this ‘reverse side’ (i.e. that which turns outwards to be photographed) dissolves into pure views (mostly of the sky) when passing through ‘The Sculpture’.

As I have already mentioned, this is an uncultivated area. Unnoticed, one might say. It is at any rate very important, I believe, for it to be done in an ‘unnoticed’ way to be successful. It must look so natural that almost no one thinks about it. For such a purpose, brick is of course extremely well-suited. So it ends up looking like a building, and in this way the constructive solutions gain authority and naturalness instead of randomness. For that is the problem when one enlarges a ‘normal’ sculpture’ to a size that one is physically able to move around in: that which in ‘normal’ size looks logical, is the expression of a necessity, becomes meaningless and radiates randomness when magnified up to the size of a building. Here, however, the constructional principles gain authority and a natural aura. To the point of becoming ‘unnoticed’.

Conversely, it is not a field in which the normal practitioners of building can give a convincing account of themselves.

Architects do not think in shapes, they think in buildings. And these works are precisely not buildings, even though they use the elements of buildings. They are meaningless. They make use of materials and methods that are normally linked to usable, useful things that no one would dream of questioning. So part of the effect made by these brick works comes from their being dressed up in the useful and sensible part of the world’s materials and methods, but retaining the inner provocation of the meaningless sculpture.

I have earlier constructed works that looked like buildings, houses, but which one could not really enter. They were monolithic, extremely large sculptures. The new ones do not look like houses. They are actually new, ungainly shapes when seen from the outside. But it is actually possible to go into them. And come out again. To pass through them.

Per Kirkeby, 1989

Gundtvig's Church (Copenhagen)

© Niels Lyksted

Håndbog (Handbook) / texts / Per Kirkeby 1991 / Around the Grundtvig Church

This is where I spent my first years. Up on Bispebjerg. Copenhagen, Denmark. The place where Frederiksborgej and Tagensvej meet and continue together out towards Søborg. Over on the other side lay Bispebjerg Cemetery’s crematorium.

On the ground floor lay a bookstore. I ran over there often and played. And also got books many years after we had moved to a completely different and distant quarter. On the corner was a dairy store with a friendly dairy-store lady. We often ran through the store. I can’t really remember what we came to when we ran through the store, a courtyard or another street — but I do remember that we ran through it. It was also safe there when we were afraid of the Germans. It was during the German occupation: streetcars drove over the plaza and there were many horse carts. Horses and horse droppings.

A long poplar avenue ran though the outermost part of the cemetery down to Utterslev Marsh. Which later played a curious, ambivalent role in my life: the wild and dangerous playground — summer in the reeds and winter on the ice — and an eerie place with children’s corpses that had been thrown out and battered. But that was not until later, especially when I had moved to a quarter that lay on the diametrically opposite end of the big marsh. The avenue here had something solemn and threatening about it. And something outdated. Which later made it easy to look at Böcklin and Feuerbach. The funeral-procession avenue.

The avenue was part of one of the axes that led up to the great church. And not the only Medieval element. Medieval understood as a kind of neo-Gothic utopia. The entire quarter had been built in the shadow of the church. There is a big church and there are little, low houses. It is Pugin’s dream of a Medieval urban society. Like a living illustration of the light — Medieval — part of contrasts. Which also fits in quite well with the fact that the church was built as a monument to Grundtvig, the Danish counterpoint to Ruskin. But just as Danish as Ruskin was English. This is why this enormous church was built with a Danish village church as its model, and not a cathedral. It is an over-dimensioned village church, said the architect. It was built from brick. By craftsmen, by masons whose equals could not be found anywhere else in the world at the time. There are no bearing concrete structures. It is also a Morris dream of good craftsmanship and human happiness. Brick is the Danish building material; we do not have any other natural material. It was those who built the Medieval village churches who used up the boulders in the moraine, so now there is only the moraine clay.

But what is truly amazing about the whole story is the time of its construction; from 1921 to 1940. This was the period of Modernism’s breakthrough. A late and wonderful anachronistic triumph for bricks. Both as an atmosphere — romantic-historic monumentality — and as a passionate cultivation of the hand’s brick in enormous textural surfaces and forms.

The housing around it is a Medieval town that lies at the foot of the cathedral, in its shadow. The Gothic-like atmosphere in the gables, portal tunnels, and little courtyards left an inescapable taste in me for atmospheric Gothic. Corners and slouching half-timbering, puppet theaters, and Doré. It has stayed with me. I am not a landscape painter; I come from a city. There are more vertical shafts and falls, ambivalent fear and The Fall — there is far more there than horizontal spread. But perhaps it is the Space in the pictures, the threatening and paradoxical, brick space that evokes some conceptions of a landscape. Because “landscape painting” has the same space, in a way behind the surface’s often harmless character. That the effect is increased because tension is so strong between the surface and the space. And landscape painting has, after all, always in principle been done from the cities.

The buildings around the church are in reality solid Danish brick structures. Perhaps the atmosphere has only emerged as a cross between the bricks’ historic burden and my childhood. Later, I saw the clear and modern brick ornaments. Such as the superb door frames.

It is more difficult to make history of the church’s monolithic and repellent forms. I be-lieve that this is where I had been imprinted with some of the structures that lie in all my pictures. Both the paintings and the sculptures. But perhaps this is my own fiction. But it is clear in any case that the church, with its dimensioning and proportions, com-pletely emancipates itself from historical illustration material. The reason for these large brick figures is Danish Medieval churches, but they surpass their models and become inexplicable. For me, the church does not belong to the Gothic, but has more of Classicism in the spirit of Boullé and Ledoux. And just like their blocks’ conscien-tious shapes that with their bodies explore and challenge the Gothic space. Which has only led them to bristle and stretch out into the space even more defiantly. [...]

Per Kirkeby